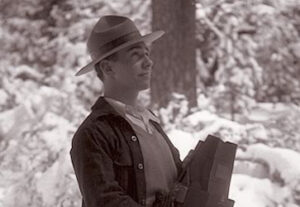

GEORGE MELENDEZ WRIGHT (1904-1936)

Born in San Francisco to a wealthy sea captain and a Salvadoran mother, George Melendez Wright developed an early interest in the natural world and earned a degree in forestry and zoology from the University of California, Berkeley. In the late 1920s he began work as an assistant park naturalist at Yosemite National Park. There he became increasingly concerned about the impact of humans on wildlife. In 1929 Wright volunteered to conduct a detailed survey of wildlife and plant life conditions in the national parks, using his own funds. He and two others began their field survey in May 1930. The survey marked the Park Service’s first extended in-depth scientific research in support of natural resource management. Their report, Fauna of the National Parks of the United States: A Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks,” formally published in 1933, was the NPS’s first comprehensive statement of natural resource management policies and proposed a radical departure from previous practices. It urged the NPS to change ingrained practices such as feeding bears at dumps and killing predators, in order to allow nature to take its course in the parks.

The wildlife survey also inspired the NPS to establish a “wildlife division” in 1933 under Wright’s leadership. As chief of the Wildlife Division, he oversaw a new team of biologists who promoted an ecological awareness. Individual parks began to survey and evaluate the status of wildlife and to identify urgent problems. Wright continued to push for park policies to preserve the animals and plants as well as the dramatic scenery. He instituted formal studies of wild species, evaluating threats and proposing solutions for endangered species.

Wright died in an automobile accident in 1936 at the age of 32. Wright who was bilingual was returning from work as part of a commission coordinating with Mexico to identify potential international park sites along the Big Bend of the Rio Grande in Texas and Mexico. He is remembered for his keen perception of ecological problems. He recognized that protected areas were not biological islands that could exist apart from the world around them and understood the significance of long-term human influences on the North American landscape. He was one of the first in his field to argue for an all-inclusive approach to solving research and management problems, rather than separating them into rigid natural and cultural resource categories. Though his life was short, his holistic approach to park management lives on through the George Wright Society, named in his honor.