5th Annual Threatened And Endangered Parks

A Rundown National Park Service

The long-held notion that working in the National Park Service was a promising, even noble, career has been shaken to its core in less than one year.

That promise under the Trump administration has been thrown into question, raising uncertainty over the durability of both the role of rangers and the innate value of nature, say employees.

In fact, despite the commitment to Park Service values and mission that many employees express, the agency long has been mired near the bottom tier of all federal agencies in the annual Best Places to Work in Federal Government due to myriad issues ranging from work-life balance to ineffective leadership, pay, and professional development.

Insufficient funding from Congress over the years certainly has contributed to hard times for Park Service employees, and many struggle to make ends meet on low salaries and often are subjected to substandard housing or long commutes. But this year a de-emphasis on the value of science that guides park management, perceived devaluing of Park Service veterans who have been pressured to exit, categorization of small park units as “cost centers,” and the proposed jettisoning of park units all have fueled a sense among employees that the agency’s very mission and how it can be accomplished are at great risk.

President Donald Trump’s determination to shrink the federal workforce and the determination by Russell Vought — head of the federal Office of Management and Budget — to ensure that federal employees are “traumatically affected” by workplace hardships have impacted employees even more harshly and pushed morale to a new low, according to many who spoke to the National Parks Traveler.

Things have gotten much worse in just 12 months, say employees from across the National Park System, many of whom reached out to the Traveler in despondence to vent their frustrations, on condition that their names not be used due to concern for their jobs.

“The NPS is grossly understaffed and has been set up to fail. Most of us are doing two jobs with no appreciation or recognition. There is a severe lack of leadership,” one Park Service mid-level manager told the Traveler. “It’s so stressful that the remaining staff are all irritable, lash out at each other, and are unhappy to be there. For me, I get a little nauseous every day when I get to the office. It’s hard to focus. Everyone is distracted.

“In short, morale is very low, if existing at all,” the employee added. “I plan to hopefully make my exit in 2026.”

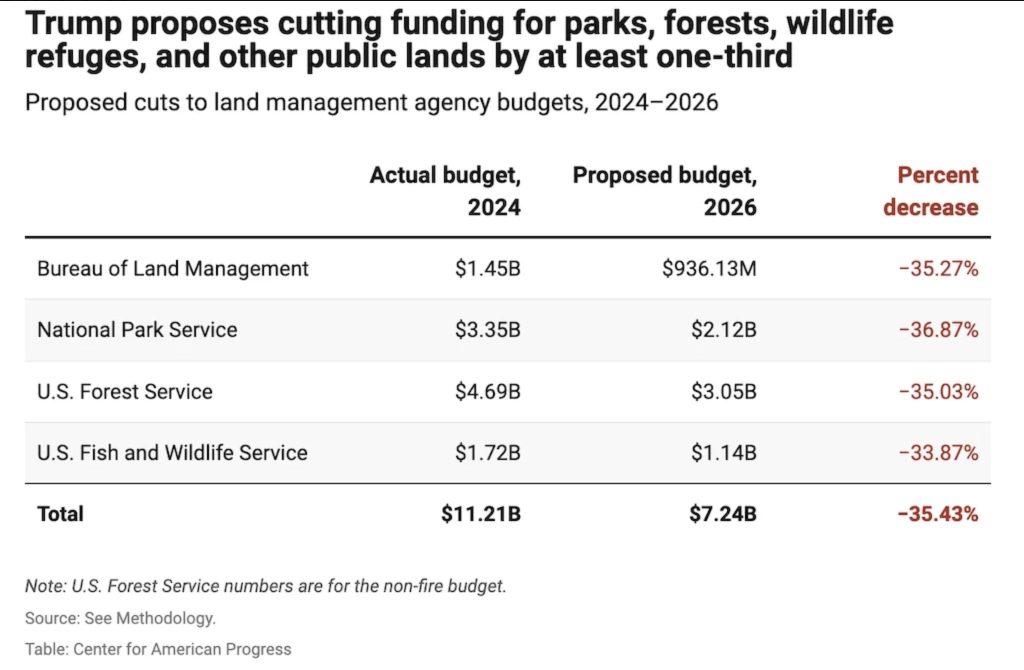

Funding Slide

From a funding standpoint, the pressure since 2011 has clearly mounted for the Park Service as Congress has added more units, visitor numbers have increased — from 278.9 million in 2011 to 332 million in 2024 — while staffing and funding have failed to keep pace.

In 2011, the National Park System contained 397 park units [e.g., national parks, national monuments, national seashores, national historic sites, etc.] and that grew to 433 units by 2025. But despite the growth of the system, the Park Service’s budget has not kept pace. While the agency’s 2011 operations budget of $2.2 billion had risen to $2.9 billion in nominal dollars by this 2025, when adjusted for inflation that 2011 number equated to $3.25 billion today, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. The Park Service’s permanent workforce, meanwhile, declined from 18,689 in Fiscal 2011 to 12,648 currently, notes NPCA.

The administration also is pulling back millions of dollars in funding that had been earmarked for projects across the Park System, including for maintenance work and conservation projects, the Traveler has learned. The move has left some regions with virtually no money to tackle projects that had been lined up for the current fiscal year.

Staff losses have long been a problem for the Park Service, but under Trump have accelerated greatly, with the loss of nearly one-quarter of the Park Service’s full-time workforce through dismissal or pressure to retire this year alone. That outstrips the pace of previous years. In August 2024, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) took the Park Service under the Biden administration to task for failing to assess its law enforcement needs, noting that Park Service law enforcement positions had declined by almost half (48%) between 2010 and 2023, with more than a 27 percent reduction just since 2021, according to data PEER obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Morale Morass

For those who remain with the Park Service, another blow to morale came in mid-December with the directive that superintendents downgrade employee appraisals due to what Jessica Bowron, the Park Service’s acting director, called “inflation of employee performance ratings.”

“For the last year, I’ve been able to blame all the madness we’ve seen within the federal government on the current administration,” an employee told the Traveler. “However, I feel the NPS is to blame for the decision to baseline all ratings to ‘fully successful’ for all employees. In short, morale is very low, if existing at all. I plan to hopefully make my exit in 2026.”

Forrest Smith was one of those who lost their jobs this past year. An engineer in the Park Service’s Geologic Resources Division, he was working on tracking down and sealing abandoned oil and gas wells in the parks when he was let go in September.

“I landed at a small oil and gas consultancy that does, basically, orphaned oil and gas plugging and methane monitoring,” said Smith. “I kind of ended up in my wheelhouse at a small consulting firm.”

Even though he’s making more money in the private sector, he’d return to the Park Service if offered his job back.

“That was my dream job,” Smith said during a phone call. “I believed in the mission of the parks. I really liked coming home at the end of day and feeling like I contributed something, like I was actually providing a service to the country overall and just, in general, the environment. It felt good, you come home and you felt like you actually contributed.”

While the non-profit National Parks Conservation Association hasn’t been able classify all the positions that have been lost, John Garder, the organization’s senior director for budget and appropriations, said that “[W]e do know, anecdotally, that positions have been lost across the board, across the table of organization, across the country, in parks and in supporting offices. At the higher levels, over 100 superintendents who manage parks have been lost. These positions are not getting refilled.”

“The biggest issue facing the NPS and the National Park System for the next few years, maybe even decades, will be the loss of many specialist positions that have been responsible for carrying out scientific research in areas such as inventory and monitoring, climate change, air quality, invasive species, history and a number of other topics; along with a reduction in contracting capability,” said Bill Wade, the executive director of the Association of National Park Rangers who had a long Park Service career. “These losses will affect the smaller NPS areas most of all.

“Along with this, I would add the loss of experienced leaders in the NPS, which will have an impact for at least several years,” he added.

Wade worries that the Trump administration’s approach to federal government will discourage people from applying for Park Service jobs in the years ahead.

Constant Fear

A Park Service employee told the Traveler that the pressures of working under constant fear of being fired and trying to manage multiple jobs, even during the government shutdown this fall, while “maintaining the highest standard of visibility and productivity for park guests,” has been unrelenting since the January 20 start of Trump’s second term.

“The administration has been unproductive, unrealistic and frankly downright against what the National Park Service stands for, which is to protect and preserve for future generations,” the employee said, referencing the administration’s personnel reductions, efforts to reduce budgets, determination to expand multiple-use of resources on public lands, altering history through removal of interpretive materials from the parks, and talk of selling off public lands. All of it has left the employee greatly disillusioned with the Park Service.

“I can only speak for myself when I say, I am a public servant honored to work for the National Park Service and was proud to take the oath,” they said. “As I stood there with my hand raised, and my new uniform in tip-top shape, I knew this was my calling and I would do anything I could to abide by that oath. Never in my worst nightmare would I sit here and decide, ‘How far will I let this administration go, unethically, unchecked and inhumane, before my morals have been diminished and my soul needs to fly.

At the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, a group that counts more than 4,700 former and present Park Service employees with more than 50,000 years of experience in its membership, Executive Director Emily Thompson said the Park Service’s ability to uphold its mission has been placed in jeopardy by this year’s “staffing and budget cuts.”

Years of budget cuts and funding shortages had left parks, and their staff, in a weakened condition when this year’s longest government shutdown in history “made a bad situation worse,” continued Thompson. “Due to efforts to gut the NPS workforce, we are deeply concerned about the ability of national parks to continue daily operations while ensuring the safety of visitors and resources, as well as the long-term impacts to science, research, history, monitoring, data collection, and other work often conducted by regional and national offices, or program offices.”

One superintendent put into context what these past 12 months have represented.

“This year brutally surfaced the stark and unresolved ideological fight facing the National Park Service: are national parks and their community programs a public trust funded by the taxpayers for the common good, or are they meant to be revenue centers expected to earn their right to exist?” the superintendent wondered.

“Generation after generation, Americans have shown their love for their national parks, yet the unanswered question is whether that love will matter or whether America’s best idea is headed for the bulldozer treatment?”