In June 1980, I began my career with the National Park Service at Fort Sumter National Monument on Sullivan’s Island. I am an African American man raised in a rural Jim Crow town of Kingstree, South Carolina, and educated at the historically Black University, South Carolina State University. I was first introduced to vibrant displays of African culture when, upon graduation, I started my position at Fort Sumter National Monument. I became keenly aware that public institutions and historic sites interpreted African American history in ways that neglected a full accounting of the legacy, history, and contributions of Africans.

My first summer in Charleston I quickly learned that many aspects of African history were hidden in plain sight, overlooked, or ignored – and were slipping away. I soon realized this cultural fragility, and, armed with my own life experiences, I embarked on a forty-year journey to connect the Sullivan’s Island community with my own Gullah Geechee roots. To those of us from with Gullah Geechee heritage, this culture wasn’t exactly hidden, but it needed greater illumination, protection, and preservation within the community.

My first summer in Charleston I quickly learned that many aspects of African history were hidden in plain sight, overlooked, or ignored – and were slipping away. I soon realized this cultural fragility, and, armed with my own life experiences, I embarked on a forty-year journey to connect the Sullivan’s Island community with my own Gullah Geechee roots. To those of us from with Gullah Geechee heritage, this culture wasn’t exactly hidden, but it needed greater illumination, protection, and preservation within the community.

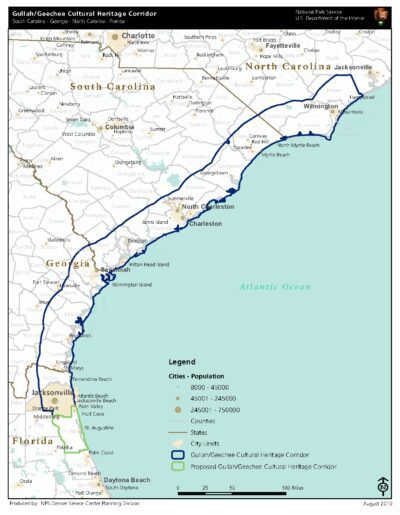

The Gullah Geechee influence is powerful in South Carolina. The Gullah people—known as Geechee in some places (and in this essay “Gullah” is used as shorthand for “Gullah Geechee”)—are the descendants of enslaved Africans brought from West Africa to work on rice and indigo plantations that extended from St. Johns River in Florida to Cape Fear River in North Carolina. The Gullah language, food, and religion came from their native homeland of Africa. These cultural identities merged with the experiences forced upon them in North America, creating distinctive and rich art forms, language, and music that has been integral to our American fabric.

In the past, the Park Service had largely neglected the Gullah presence in their interpretations of Fort Sumter National Monument’s story. Not until 1992 did the Park Service reevaluate the park’s story and forge a partnership with Gullah Geechee grassroots communities in the East Cooper area to address this grave oversight. But the newly formed relationship faced many challenges because of the rooted mistrust and suspicion of the Gullah Geechee people, who had long borne witness to historic sites inaccurately presenting their history.

The increased interest and emphasis on the Gullah culture at Fort Sumter prompted a shift in the interpretation at many historic sites. Through careful planning, the Gullah communities in the Charleston area built new partnerships with local historic sites. In the late 1990s, a group of individuals from the Gullah Geechee community, local historic sites, the Park Service, and the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission created the Gullah Geechee Consortium to foster better communication and relationships between historic sites and Gullah Geechee communities, marking the start of earnest dialogue and trust between the two entities. Employees at historic sites sought input from Gullah communities, requesting stories from their perspectives. This new partnership laid the groundwork to explore Gullah Geechee culture through a special resource study conducted by the National Park Service. Entitled “Exploring the Soul of Gullah Geechee Culture,” the special resource study shined a national spotlight on the significance of Gullah Geechee culture in American history, shifting how Gullah Geechee history was interpreted, viewed, and respected in the community. It gave voice to a people and culture whose history was often devalued, marginalized, and ignored.

The journey to uncover what was hidden in plain sight began in the basement of Mother Emanuel AME Church on May 9, 2000. I had organized the meeting on behalf of the Park Service, and selected the location, knowing it was a safe space where the community could and would speak freely to Park Service officials. During that first meeting, Gullah communities and the Park Service together established the goals and mission of the resource study.

Community members supported this effort, though some were still suspicious, having experienced similar promises with no results. But, because they could see that I had long been working to restore trust, respect, and healing to the Gullah communities, they were willing to wholeheartedly support the study. The next six years yielded public meetings occurring across the fertile crescent, starting in Wilmington, North Carolina, and extending to the coastal areas of St. Augustine, Florida. It was a process both fruitful and rewarding.

The Park Service, with the Gullah communities, led and guided the creation of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor stretching across southeast North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and northeast Florida. Through the leadership and tireless efforts of U.S. Representative James Clyburn, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor was established in October of 2006.

Presently, the Gullah communities have a voice and a vehicle to preserve, recognize, and share their culture across the United States. The development of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor spurred other governmental and grassroots organizations, nonprofit agencies, and historic sites to connect with their local Gullah Geechee communities.

Michael Allen served as a Park Ranger, Education Specialist, and Community Partnership Specialist for The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor/Fort Sumter National Monument and Charles Pinckney National Historic Site. He is currently a member of the Executive Council of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks.